Memories fade with us. The memory remains. Memories cannot be handed down, they are part of us and we take them away with us. Memories are documented, handed down and it becomes history. It is then up to those who have lived that story to tell it and, as per the study method, to research it. It is the research that animates the story, enriching it, providing more and more documentation, which certifies its truthfulness and reliability.

Thus, today, having tools that allow you to do research, probe the corners of the globe and…

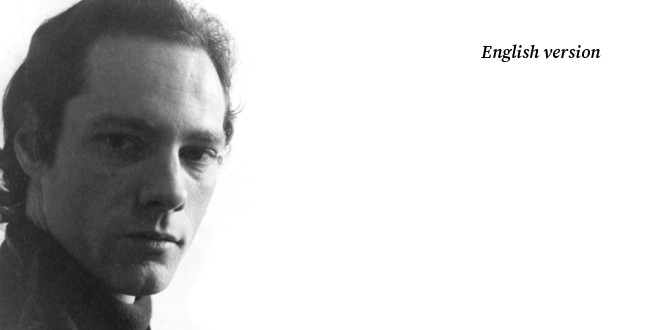

Richard Lee, dancer, choreographer. He is the one who answers the following interview: the master.

It’s the most creative and exciting art of the theater: dance. Perhaps the most difficult to represent because it is the body that “speaks”. An ancient form of communication, mimicry, dance “dances” gestures. Is it still like this in dance today?

To summarize a bit, dance is mainly a physical activity in which the performer is both product and instrument. Even before speaking of technique, the complete fusion of body and mind is the goal of all training. The mind has to tame a body that sometimes wants to act for itself, “au hasard” or out of habit, to merge into its own physicality, creating a state in which it is not possible to distinguish an autonomy of either.

In the hall or on stage, there are three things I appreciate. In the first place, precise and accurate training. That is, the dancer who is master of his vocabulary, classical, modern, whatever it may be, who knows how his body works, and who proves himself not only capable of technical feats, dazzling as they can be, but exercises almost artisanal control and mastery about the movement in the smallest details.

For the possibilities offered by good training to be realised, it takes concentration, or rather, the ability and dedication to focus, to be “present” or “merge” into the movement, thus nothing just “thrown together”. Finally, no art can be really interesting, can really justify itself, without risk, but a risk taken with prior preparation

For me, what sustains the “gesture”, the “communicativeness” of dance understood in any sense, is something I would like to call “cantilena”.

Close to the use that Elena Tchernichova makes of the term, by cantilena I mean the almost unconscious control of the quality of the movement, the ability, and also the intelligence to develop a long line, indeed a line of any length.

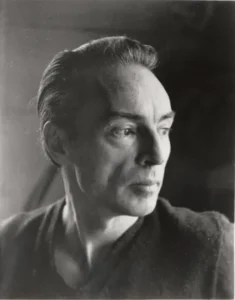

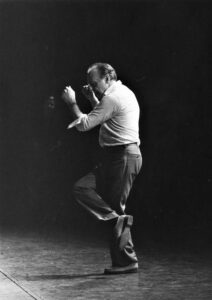

George Balanchine

It is the “being in the movement” and a faculty necessary for musicality. But much more, because for me expression, it may seem paradoxical, arises and emerges from the movement and not the other way around, the emotion that determines the gesture.

You, maestro. The beginnings, and a nostalgic question: shall we pay homage to your masters?

For me, as I believe for many others, once I discovered this particular form of theater, becoming a dancer was not so much a choice as the affirmation of an existential exigency.

And this is especially true for those who, still like me, did not grow up in a famous theater or train in a great school from a young age.

Having said that, even if it seemed anything but from the outset, luck smiled on me in the sense that I was time to work with exponents of the Ballet Russe in the United States that were still active. For example, Natalie Krassovska, who very generously taught me the pas de deux from Don Quixote. Picture this: alone in the studio and dancing with me! Later, I worked personally with choreographers such as George Balanchine, Anthony Tudor, George Skibine, and many others in the golden years of the dance “boom”.

There is no doubt, though, that I owe my career to a handful of key teachers.

I had already danced with the Houston Ballet, Pennsylvania Ballet, Atlanta Ballet, among others, where of course I also studied, when I met Perry Brunson. Also an ex-member of Ballet Russe, he taught at the Joffrey Ballet school in New York.

Brunson’s lesson, like those of all the great masters I’ve known (some more, some less) did not present itself as a mere series of more or less interesting and stimulating steps.

On the contrary, it was structured, explicitly, I repeat, explicitly, precisely to develop strength and “placement” together to obtain maximum control over the quality of the movement and therefore expression.

In Paris I took Raymond Franchetti’s class for at least a dozen years, and it would be difficult to express how much I owe him, or rather how much I owe to those classes.

The make-up of the ten o’clock class, for which the wonderful Elizabeth Cooper played, was quite heterogeneous, from the étoiles in the front to adults in the back who just tried to follow along.

Incredibly, however, year after year everyone made progress, according, of course, to their different possibilities! Here too (Franchetti corrected little), as with Perry Brunson (he corrected a lot), it was the very structure of the lesson that produced the results.

The contribution of Maggie Black and Lawrence Rhodes, however, is on a whole other level. The latter, who was one of the most important exponents of classical dance of his generation in the USA, as well as a person of great humanituy, began to think seriously about teaching just when he was dancing in Italy with Carla [Fracci].

Carla Fracci

During our tours with “Giselle” and “Romeo and Juliet” (1974 – 1976) he began teaching company class, employing technical innovations based on a new understanding of the musculoskeletal functioning of the body in movement, learned from Black.

In a certain way, it confirmed my conception of ballet technique. In the longer term, especially after studying with Black in New York while dancing with Stars of American Ballet, it served as a rationalization and foundation for a method that I then applied as a teacher myself.

You are the “son” of the classical repertoire. Generation of dancers of the important choreographies of “Corsaire”, “Sleeping beauty”, “Romeo and Juliet”. The dance of beauty, of cultured and refined iconography. Over the years there has been a search for new choreographic languages. George Balanchine was a pioneer. But is dance story or intuition?

You are right; basically I am a “son” of the classical repertoire, at least in the sense that this is how I have always defined myself. “Swan Lake”, “Sleeping Beauty”, “Sylphids” and all the other classics, were my dream from my first lessons and in various roles and in different companies, I danced them all. What can I say, is it the usual story of the country boy who wants to be a prince?

I was born in a big city, unfortunately also very provincial, to parents who had no idea that there was such a thing as ballet, even though my mother was a musician and a university graduate (1930s, when very few women went to university).

So, my story in dance begins there, in 1962 with the first ballet I saw live, “The Golden Cockerel”, a danced opera by Rimsky Korsakov. I was so impressed that I decided right then and there that I would attempt a career as a dancer.

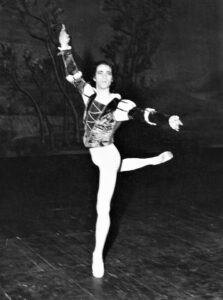

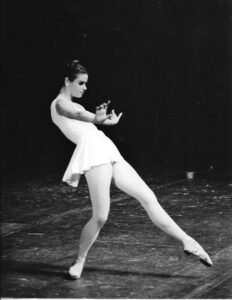

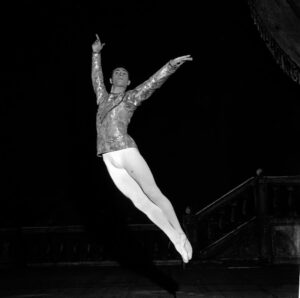

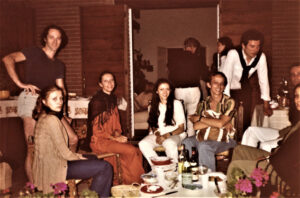

Richard Lee

These were the first years after Rudolf Nureev‘s defection. He was everywhere, even a lot on television; I will always remember the evening I saw him with Berisosova in “Diana and Acteon“.

It was clear that so much was changing in dance, especially for men. It was not the first time, of course, but the moment seemed propitious for me, full of possibilities.

However, better to talk about choreographers perhaps, the dance makers, and for now those that clearly fall within the classical tradition; we can think of talking about the counter-currents further on perhaps.

As you mentioned, choreographers have contributed enormously to the development of ballet in the 20th century, starting with Fokine and then certainly George Balanchine and Anthony Tudor, to name two with whom I have had the honor to work.

As for my relationship with Balanchine and the repertoire he created, I have to go back to the 1963-64 season. I was studying at the Metropolitan Opera ballet school, and I had the chance to see all the ballets that the New York City Ballet was performing at City Center that year. To say I was impressed would greatly understate the impact that season had on me.

Balanchin’s language is clearly classical (he, product of the Russian imperial school), for the technique and for the very conception of dance theater, but it is also dialectical in scope, as it responded to its times.

I have always found the coherence with which he managed to recreate the musical space in the physical space through movement and dance extraordinary.

In what other choreographer is this always, always so close a relationship; let us remind ourselves that Mr. B. also studied piano and composition at the conservatory.

For example, his “Concerto Barocco” stages the concerto by J.S. Bach for two violins and results in three movements of uninterrupted beauty not only for the structural figures of the choreography but the individual combinations he invented, but more than anything else for the sheer musicality of the whole!

Moreover, my assumption which I always see in Balanchine’s ballets, is that dance is not only movement in space; indeed, dance is movement that creates a space!

However, it is always useful to remember that this space still demonstrates a particular cultural-historical attribute: it is always a hierarchical space that rewards the “center” over the “periphery”.

On the other hand, it should come as no surprise that some of Balanchine’s ballets were stripped down over time, as a response to the evolution of aesthetic tastes.

For example “Apollon Musagète” and the same “Concerto Barocco” have lost their heavy costumes and have gradually achieved their present minimalism without distraction, which highlights both the overall choreographic structure and the contribution of, and the relationships between the individual dancers. Of one thing there is no doubt: Balanchine’s ballets are beautiful to dance!

Merce Cunningham

Of course, dance can tell a story, it can cheer us, it can arouse feelings, empathy, and any number of sensations. In this sense, Prokoffiev’s “Romeo and Juliet” has followed me and enriched my life since I bought a record of it as a boy (but what an irony, with Merce Cunningham and Carolyn Brown on the cover).

I danced it in the Skibine version with Vera Kirova, then with Carla in Italy (in the role of Paris) and it still fills me with joy today when I think about it. My last encounter with this tragedy, as Romeo, was in Roberto Fascilla‘s grand pas de deux to the music of Berlioz.

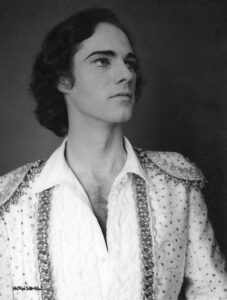

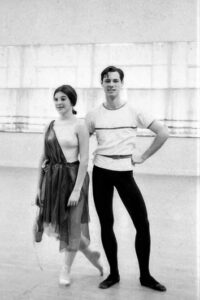

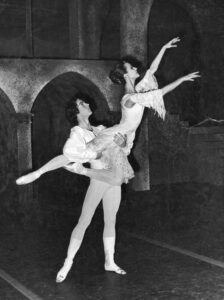

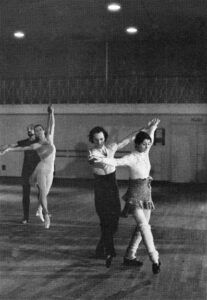

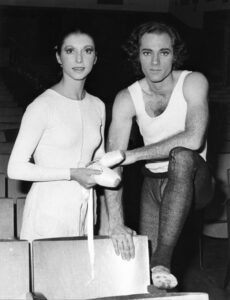

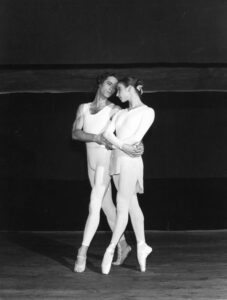

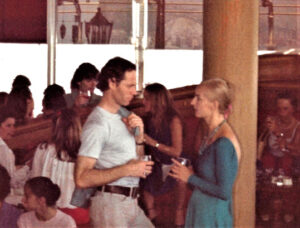

Richard Lee, Vera Kirova

However, dance can also “mean”, that is, represent the human condition and social situatedness on a completely different level.

A ballet like the aforementioned “Concerto Barocco” shows a construction that we recognize as “rational” with classical technique, a three-walled stage, and supposes an institution, a company, for its production.

It is therefore historically a product of the western modern age that expresses the way that we feel we live in the same “world” not only as a Petipa, but also as a Vestris, a Monteverdi, a Newton, a Galileo or a Descartes.

In Geneva I not only had the opportunity to work with Balanchine for “Four Temperaments”, “Serenade”, “Symphony in C” and many others, but also to get to know him more personally.

Like so many greats, he didn’t put on airs; he worked, created, and respected those who worked with him, and cooked a very good blanquette de veau! I worked with Anthony Tudor in Pennsylvania Ballet and also at the Grand Théâtre; he was alone in Geneva and often came to dinner at my house.

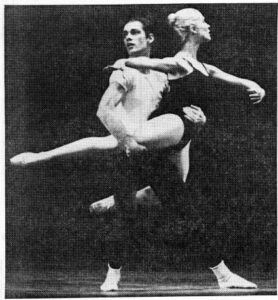

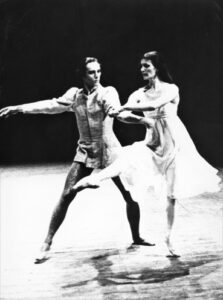

Richard Lee, Carla Fracci

I knew him as a fascinating, cerebral man. But as is well known, it could be difficult and even cruel!

He is known for his dramatic ballets, however he did not want drama and feelings to be communicated with facial expression, but instead had to come from the whole body; according to him, everything developed through movement.

My story, therefore, is divided between the Balanchine repertoire and others, but always of a classic nature, and then the great classics themselves. In Belgium and above all in Italy, I devoted myself, with great satisfaction, to the traditional repertoire.

It is certain that fate played its part, but my trajectory was also the result of a series of precise choices made every time a different path presented itself. Risky, but you only live once!

For example, at some point I could have auditioned American Ballet Theater, and had a good chance of getting in, and thus having a more secure future. But the idea of joining that company and immediately finding myself performing Agnes de Mille’s ballets (important as they were), didn’t thrill me; it wasn’t for me.

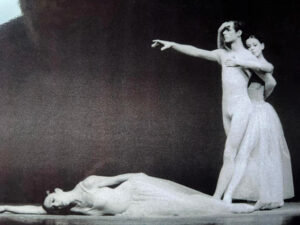

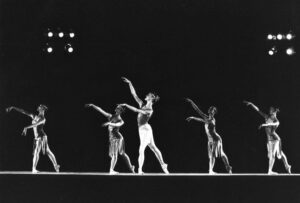

Patricia Neary in “Apollon Musagète” (Stravinsky/Balanchine)

Ph. Richard Lee©

The previous question has a reason: the “difficulty” of transposing the message of contemporary dance is often not immediate. The spectator needs to be prepared to decode the action danced on stage. The American Ballet had already in the 1940s, revolutionized classical dance. Do you find that revolution in contemporary choreographers today?

My aspirations were well centered on the classics from the beginning; only much later did I begin to investigate that attitude of mine rooted in a profound Enlightenment identity.

However, I include in this classic constellation the Balanchinian repertoire and all those others that I consider to be mostly extrapolations of that tradition: a close relationship with music, beauty or psychological or social commentary as an end, and different roles for men and women, etc.

It is equally true that the twentieth century saw many attempts to renew a vocabulary that for many seemed old and musty, with little relevance to today’s world.

Martha Graham

The aforementioned De Mille produced strictly “American” ballets such as “Rodeo”, “Billy the Kid” and “Fall River Legend”. Others, like Lew Christensen’s “Filling Station,” were based on characters and gestures from everyday life. On the old continent Roland Petit left us “Le jeune homme et la mort” which also incorporated common gestures.

And, heralding and unprecedented for 1946, it was choreography created before the music was chosen! Perhaps little remembered today, in his long career he also made a series of works that refreshed the tradition of narrative ballet.

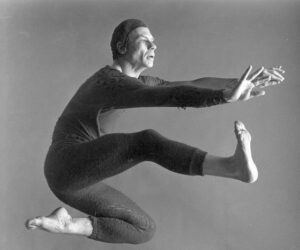

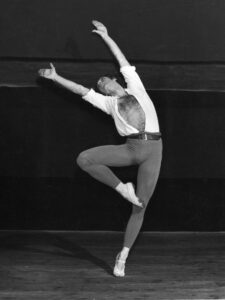

Richard Lee

Closer to home, I greatly admire the work of Jiří Kylián for the beauty of movement, the gratifying structure of his ballets and the skilful use of dancers; I have seen his company many times with pleasure.

And there are others, like Nacho Duato, but nowadays, I’m fascinated by the work of Crystal Pite.

I find her masterful conception of stage space particularly seductive, which becomes explicit when she employs large masses of dancers.

She also knows how to handle solos or small groups. Among many others, her “The Statement” is stunning, a “Green Table” for our day!

Nonetheless, there is undoubtedly a “difficulty” with contemporary dance. Classical dance expresses, indeed has participated in five centuries of socio-cultural development and in this way acts on a background of “conscience collective” above, or rather below, any normal interrogation.

We do not pay much attention, but this “common sense” includes, for example, the binomial beauty-nobility and a structural element, the pas de deux, in which the woman sees herself “normally” supported by a man.

Modern or contemporary dance, on the other hand, in many ways represents a challenge to many clichés that classical dance carries with it as baggage. Technically, the ballet dancer stands up, as one would hope at least.

From the beginning, modern dance incorporated the fall, indeed it incorporated the very idea of the fall, work on the ground and possible recovery, as primordial realities in its choreographic language, also I might add, as it corresponds to life.

It would be useful, perhaps, from Duncan to Graham, to talk about “expressive” rather than modern dance. Indeed, they renounced beauty for itself, but in common with classical ballet they admitted a psychological or emotional underpinning.

By now the public is able to understand the work of these choreographers, because once the impact of a different technical vocabulary has been overcome, the same background, even when it is stripped of gestures, is recognized.

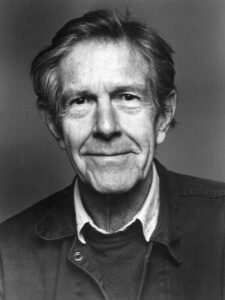

John Cage

From the 1950s onwards, it is a completely different story! Starting with Merce Cunningham it is certainly understandable that audiences remain confused, or worse outraged.

To enter this bewildering world without footholds one must at least have some knowledge of and accept a specific intellectual attitude, first and foremost, that of John Cage, the composers of the New York School and the abstract expressionist painters, non-literary, non- linear, where risk and uncertainty are in the forefront, without narrative or psychological background, where dance, music, and stage set-up coexist, as it were, in parallel, without necessarily determining a common trajectory.

Sounds and movements exist for themselves, not as vehicles for feelings. At the time, the dancers involved in this approach to theater did not find it dehumanizing, rather they found it liberating.

And then in the 1960s came post-modern dance which not only rejected expression, but also the techniques that served it, preferring natural movements. Impossible that all this would not arouse dismay in the public.

But what does it mean? First of all, I am convinced that classical dance, based on the great classics and the repertoire that was later produced with the same assumptions, will not disappear.

Although it belongs to a precise historical era, it expresses a way of seeing and living that will remain not only as a residue or archaeological artifact, but also as an omnipresent social resource.

Roland Petit

Beauty, honor, love, and alas, sadly even the basest feelings, I do not think have an expiration date, at least not in the foreseeable future.

How can we think that the freshness, the joie de vivre, the joy of dancing so enthralling in a piece like the exquisite “Dances at a Gathering” by Jerome Robbins can ever go out of fashion.

Having said that, I must also confess that yes, in my opinion, something is “moving” though. The new forms announce and are part of a fundamental transformation of our modern social structure, certainly an object of struggle, but unstoppable.

Of course we don’t know what shape the future will take, but all cultural forms, including dance, will be involved in its construction.

Roland Petit, Maurice Bejard, Martha Graham, Twila Thurp, Merce Cunningham, well-structured artistic identities. Modern dance and the cultural revolution of ballet. Two generations have passed since these myths and posterity can be found on the stage proposing tormented expressive codes. I understand that societies change (or get involved), but the beauty of the drama of love is no longer sought. Things? Existential or artistic crisis?

It might surprise you, but my first lessons were in modern dance, Graham technique, because in my city of San Antonio (TX ed.) there were no classical dance classes for boys at the time! In any case, it was not the kind of dance that appealed to me, and what is more, it did not suit my body.

Nevertheless, during the 1963-64 season, when I was enrolled at Princeton University, I had one of the most exciting moments I have ever experienced in the theater, seeing Graham herself in New York, still dancing at nearly seventy, in “Clytemnestra”. I still get shivers down my spine thinking about it.

Roland Petit, of whom I have already spoken, I met on tour in Turin where I was able to appreciate his “Coppelia”. Although I was already working in Italy, I confess that I gave the company some thought…

As for Maurice Béjart, he has always seemed to me a great man of the theater and some of his works still “speak” to me: among the many, I adore “L’Oiseau de feu” and “Le chant du errant companion”, the latter practically a pas de deux for two men.

However, my only direct and sustained encounter with contemporary dance was the year I was a member of the French company, Les Ballets Félix Blaska.

Félix had a wonderful group of good dancers, all classically trained, and above all interesting. In addition, his choreography was generally very successful, musical and sometimes very witty.

At the end of that contract, invited by Patricia Neary, I was to return to Geneva as a soloist where I would have performed many other ballets in a repertoire that I loved so much. But unfortunately the oil crisis broke out and all new contracts were canceled in Switzerland. Instead, I landed in Bologna; the rest is history.

Patricia Neary

Much later I began to appreciate Merce Cunningham‘s works, including those based on his affiliation with John Cage, which I had first seen in the 1960s.

Apart from the truly fascinating socio-cultural setting of his work, certain pieces, such as “Summerspace” and “Suite for Five”, were of great beauty in themselves, and Carolyn Brown, the great interpreter of the repertoire created by Cunningham, I always liked very much.

A method based on the “uncertainty principle”, I can even admit, but the absolute split between music and dance, fundamental in the aesthetics of Cage and Cunningham, I have never believed in, perhaps not even Merce did. There is always a relationship between the dancer and the music they move to!

I went to college with Douglas Dunn, ’63-’64. Douglas became, and still remains, one of the leading exponents of post-modern dance who affirmed that any movement is “dance”.

He was, is, three years older than I, but we took lessons together at the same little dance school there in Princeton.

One could not conceive of two more different careers, two more divergent professional trajectories, in dance.

One, mine, classic-romantic, affirmed, and retraced, a certain historical narrative of the modern era, i.e. from the mid-15th century onwards, based on logic and rationality, progress and individualism together with the autonomy of the subject human.

The other current, on the other hand, in various guises and different genres, during the 1900s showed itself to be skeptical of all these values.

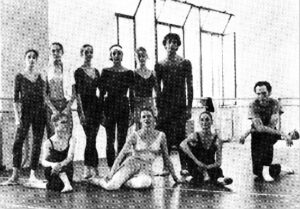

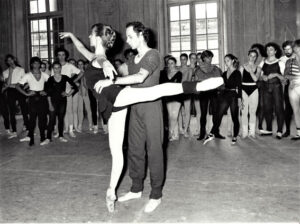

George Balanchine rehearsing “Four Temperaments”

Ph. Richard Lee©

For a direct answer to your question, I cannot conceive of any art form detached from the social formation in which it is immersed and of which it forms a constituent element.

That is, to begin to understand the state of ballet today, I have to do my best to push back against the tendency to think of it as only an “object of beauty,” or “entertainment,” or even “expressive language.”

All right, it will be all of these things, but it also has, and has always had, a very strong political-social charge, and not only through its content.

This is carried and expressed in the very form, the structure, of its particular technical and conceptual system of the theater, accepted for centuries as an out-of-time, natural fact, an analogy would be the tonal system in classical music. A book is certainly hidden in there; who knows, maybe I still have one in me!

Maurice Bejart

Your dancing was one of love, romantic, dramatic, cheerful. Going to the theater was a pleasure. Watching the physical evolution of a dancer was amazing. The dance, by heart, was lightness. It seems to me that today dancers don’t fly anymore. Is this the evolution (or revolution) of classical dance?

Today we have the opportunity to appreciate and evaluate our history since at least the beginning of the 1900s through videos accessible to all online.

There is no doubt that there is more of everything: more pirouettes, everything more “open”, higher extensions, “passés” that have climbed from the mid-calf up to the knee and beyond, “jetés” that end up as splits in the air, often of more than one hundred and eighty degrees(!), making them impossible to bind fluidly in an enchainement.

One thing that the dancers of the past had was the “ballon”, above all in descent. It is clear that I have an opinion on this evolution. I’m not interested in the “most”, the highest leg, the most numerous laps, if that cantilena I mentioned earlier is missing.

Europe. An important step in your career. Milan. Carla Fracci. Romeo and Juliet. Driven to leave the US for the “old” Europe. For profession or history?

From an early age I knew that, in one way or another, at least part of my life, I would have lived in Europe.

Before even dancing, I was studying French, instead of Spanish which was spoken by a large part of the population of my hometown. However, I arrived a bit by luck and a bit by choice.

Loredana Furno

Fate decided that when I returned to New York after a season with the Atlanta Ballet, there was absolutely no work. I studied at the Joffrey Ballet school, learned the repertoire, and attended rehearsals.

But here, I have to interrupt to insert a note on the way union contracts (AGMA) were structured then in the USA.

There were two types of contract, one for companies employing up to forty dancers, the “small company contract”, and one for companies with more than forty dancers, the “large company contract”.

The expenses involved for a “large company” were much more onerous than those for a “small company”. Joffrey was a “small company,” and therefore found itself limited to only forty dancers.

We were three men in line for the company, but there were only two contracts available without crossing the forty threshold. Unfortunately, as I was the last to arrive, I would have had to wait for the next season.

However, while it seemed that one door was closing, another was opening. This time the wheel of fortune turned in my favor.

Balanchine accepted a consultant position for the Ballet of the Grand Theater of Geneva (he was an old friend of Herbert Graf, the director of the theater) and the ballet master he sent wanted to integrate American-trained dancers.

Overjoyed, I was hired, and stayed three years in Geneva, where I also worked as a photographer both for the theater and for two newspapers. Then, I did a season at the Ballet de Wallonie in Belgium, where I went by my own choice rather than accepting a contract in Germany.

After that, I toured for almost a year with Les Ballets Félix Blaska. Bologna turned out to be a happy stopgap compared to the contract lost in Geneva. What a memory, the employment office in Milan!

Roberto Fascilla

I met Carla Fracci and Beppe Menegatti the very morning of the first rehearsal for “Stone Flower” in Bologna, 1974. Beppe came up to me at the bar and said to me in French, “C’est vous, vous êtes l’américain” (I spoke fluent French, but not a word of Italian) and he immediately introduced me to Carla. They already knew I was there; Carlo Faraboni had undoubtedly announced it to Beppe!

Beppe later told me that I shouldn’t sign any contracts without talking to him because from then on, I would be working with them. For me, it was my dream come true.

Carla was always very generous with me. It is true that I had a precise function in the Fracci/Menegatti productions, that is, the second trusted partner.

Dancing with her could be exhilarating, but it was also a heavy responsibility, one that I took very, very seriously; nothing could go wrong.

After all, the pirouettes, lifts and everything he did with me were the same as she did with the etoile dancing with her. In any case, I believe we had a good professional and, as far as possible, personal relationship; she told me I was “a romantic”!

Of “Romeo and Juliet”, I think it was one of the happiest realizations of a narrative ballet produced anywhere in those years. It married Cranko‘s four pas de deux (three with Romeo and one with Paris) to Fascilla’s perfectly timed choreography.

In my opinion, and I’ve seen many, Juliet was for Carla, with Giselle, a role in which she did not have, and still does not have today, any paragon.

But there was more. Alongside her lined up a truly perfect cast: a Romeo who responded to my ideal in James Urbain, virile and strong, who in any case did not lack gentleness, a great Lawrence Rhodes who, through his technical skill and depth of expression, made Mercutio live, and Fascilla himself who embodied Tybalt perfectly.

Even in supporting roles one could not have expected better. Anyone who saw it must consider themselves lucky to have participated in a moment when Italian ballet reached its peak.

Beppe held so many reins in his hand and indeed, without him their great undertaking of bringing high quality ballet productions everywhere, including the smallest towns, would never have been possible.

Just think, we did “Romeo and Juliet” even in Budrio where there was no place on stage for the scenery. It was a cultural policy in which they both believed.

And I am very proud to have contributed with my small part, and not only with them; for example, with Margherita Mora, we presented the pas de deux of “Sylphides” and “Don Quixote” on a tiny stage in Ostuni, with costumes by Brancato (Milan tailoring for theatrical costumes ed.) though!

An intellectual with a remarkably quick wit, Beppe knew how to deal with theaters and knew, indeed loved deeply, theater people.

Little anecdote: after a rehearsal that went badly (it happens), with general morale that could not havee been lower, the whole company was sitting on the stage waiting for the next rehearsal to start.

And here comes Beppe like a farmer who was sowing his field, only that Beppe scattered candies from a paper sack saying: “Come on guys, life is beautiful and we’ll put on a wonderful show”! Of both of them, Carla and Beppe, I will always have a great affection and many wonderful memories.

Speaking of those years of dissemination and democratization of entertainment in Italy, I must mention Loredana Furno and how and how much her collaboration and friendship were precious to me.

We danced a bit of everything, a bit everywhere, from Monteverdi‘s “Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda” and Stravinsky‘s “L’histoire du soldat” to many classical works including a creation made especially for us, “Adagio” by Loris Gai to music by Shostakovich.

Loredana Furno, Richard Lee

Memories: Niccolò Piccinni Foundation, International School of Ballet, Balletto del Sole. The sun of our city. Petruzzelli. Your dancers, your students. Would you be surprised it I told you that you many still remember?

With Carla and Beppe, we took “Gisele” to Bari, to the Petruzzelli Theater, in the autumn of ’74. I immediately liked the city, both old and modern, with its seafront that would later host many of my walks and the theater, which could perhaps seem a little shabby, but to me looked wonderful, and indeed, it was! The audience was enthusiastic and obviously thirsty for ballet.

Who among us will ever forget how the musicians in the orchestra took turns playing so that those who were not playing could stand up to see, not just in passing, what was happening on stage, and perhaps even get a glimpse of “la Fracci”.

The Fondazione Concerti Niccolò Piccinni, a family business, brought us back several times and I have always had excellent memories of Maestro Gianvito Pugliese, a man of great class as well as being a unanimously esteemed musician.

At a certain point, the Foundation decided to establish a presence of classical dance studios in the area, with the aim, they said, of professionalization. Roberto Fascilla agreed to direct the company and asked me to go there as Maître de Ballet and teacher in the new school.

We did everything we could to achieve the goal, including performances with well-known professionals together with the group they called “The Corps de Ballet of the N. Piccinni Foundation”.

The group, not very large, only one class, worked with great dedication and diligence. Unfortunately, the Foundation did not feel like going beyond a certain point (or level of investment) and it was at that moment that the idea of the Balletto del Sole and a school for serious and uncompromising training linked to the company was born.

On paper, the idea was flawless: Bari, an important city with a very enthusiastic audience for ballet, a beautiful traditional theater (that is with no resident company), and all without any professional institution of classical dance.

I have wonderful memories of the students and of the work in the studio, and I still find it very gratifying that those who studied there had the utmost of my commitment and that some of them were able to continue and make a career.

As for the company, we planned a repertoire with ballets by choreographers of international standing and for a young company, the first results on stage were promising.

For the first season we presented ballets by five different choreographers and iwith the successful mounting of “Waltz Fantasie” in the second season, I received Balanchine’s personal permission to mount any of his ballets I could cast.

I had planned to expand the repertoire for the third season with at least “Concerto Barocco”, “Pas de Dix”, a ballet by a European choreographer (as I had done with Heinz Spoerli by presenting his “Wendung” for the first season), and a piece of a young Italian.

These seemed appropriate to attract and satisfy our audience and give dancers the opportunity to grow.

And for the following year, I would have liked to present Balanchine’s “Apollon Musagète” in Magna Graecia. I am pleased, at least, that the talented young man I had in mind for the latter danced it successfully elsewhere. Well, you can always dream. But it wasn’t to be.

Rai3 in 1982, dedicated a focus to you during a summer event in Matera. The Compagnia Balletto del Sole presented “Valse Fantaisie” by Michail Glinka with choreography by George Balanchine and reproduced by Patricia Neary and “A pretty girl is like a melody” and “Sunset” with your choreography. Tribute to Maestro George Balanchine and a tribute to the beauty of dance lived and danced with irony and joy. We all experienced the lightness, the satisfaction of dance. Dance today, today’s young people, the choreographers… you, maestro, what considerations do you have?

I am now retired from the university where I spent thirty years as a professor of sociology and director of a research center of international importance.

I can only be satisfied with the professional balance sheet of those years in academia. Dance, on the other hand, has always been the passion of my life and Italy the land of my heart.

Theater is made with others. And so I would like to end with a small reminder underlining the importance of respect, friendship, even love, and the value of the community in which we work. Theater is, in fact, a community of life beyond being a notable profession.

In terms of training, it cannot be denied, as mentioned above, that today’s technical performance is much higher than it was forty years ago.

However, I do wonder, even if only rhetorically, if there hasn’t been a cost: first of all in the quality of the movement we talked about before and then in the assimilation of the tradition, the two qualities that in my opinion develop over the entire arc of an artist’s maturation.

There is certainly the fourteen-year-old able to perform a variation of the classical repertoire, but would that young person be just as convincing just walking across the stage?

In any case, more often than not that variation will be presented on a bare stage in some competition! Okay, competitions are now a reality in dance, and undoubtedly have their “raison d’être”.

In any case, it may be anachronistic of me, but I find the solution offered in the long-term by “stages” (something akin to a dance camp) more positive than the various “prix de …”!

And Italy can boast of having hosted the iconic specimen, the Stage Internationals di Danza together with the International Ballet Festival, in Nervi.

The desire to do, to work, to learn, to make acquaintances, to exchange ideas gave life to an incredible positive energy.

All levels were welcome, and the very best teachers participated. The beauty was that even if the impression was of a great fair, a rousing fete, the assumptions could not have been more intensely serious

So ky very best wishes to all those who have chosen or will choose dance, including those who, like me, feel chosen by dance. Dancing is human nature.

This interview ends gracefully, considered another page in the history of modern dance.

Richard Lee is still today, one of the active testimonies of a dance of the late twentieth century, which made the dance art the most exciting art of the theater.

A teaching is learned and remains in memory, the absolute dedication of a dancer whose aim was to transmit his inner experience, as a life lesson.

Gianni Pantaleo.

Le immagini e i testi potrebbero essere soggetti a copyright.

Arti Libere Web magazine di arte e spettacolo

Arti Libere Web magazine di arte e spettacolo